Huffman Coding with Compressure

Introduction

Storing and transmitting data is a fact of life in the modern world. Often it would be nice if we could shrink the amount of space the data takes up, so we could transfer it more quickly or so that it wouldn’t fill the disk right away. The process of shrinking data is called compression. When discussing data compresssion there are two main categories: lossless, and non-lossless (or lossy, for the initiated). Just as it sounds, lossless data compression is a form where the entire full set of pre-compressed data is still somehow encoded in the compression (example: .zip files). Lossy compressions are flattenings of the original data that would pass adequately for the original thing (example: .mp3 files). This project deals exclusively with the lossless compression algorithm called Huffman Encoding.

Huffman Encoding

The Huffman Encoding method was first described by David Huffman in the early 1950’s [1]. The algorithm takes fixed-length data and converts each symbol to a variable length code based on the number of times the symbol occurs (symbols that occur more often get shorter codes, less likely symbols get longer codes). For the sake of demonstration we will assume that the data we’d like to compress is pure text data, encoded in ASCII or UTF-8. For more information about how ASCII encoded text works check out [2] and [3].

In ASCII each character in a text document is 7-bits long, and in UTF-8 a character occurring in the ASCII alphabet is encoded in 8-bits (1 byte). This encoding gives all characters equal weight, leading to an inefficient (although conveniently standardized) storage method. By giving each character a variable length code we can reduce the number of bits required to store the data, hence compression. To do this we will begin by constructing the Huffman tree. We will use a simple method of building the tree with a priority queue that has a time complexity of O(log n). There is an O(n) method of building the tree if the symbols are sorted by the frequency which they occur, but we will not worry ourselves with it.

The first step to building the Huffman tree is to count the number of times each character occurs in the data set we are trying to compress. Once we have the characters and their frequencies we will build the tree. Each of the leaf nodes of the tree will contain one of the characters and the number of times it occurred in the data. We begin by putting each of these nodes into the priority queue:

for(int i = 0; i < charFreqs.length -1 ; i++){

if(charFreqs[i] > 0){

huffQueue.offer( new HuffmanTree<Character>((char) i, charFreqs[i]) );

}

}Then we can build up our tree by popping two elements off of the queue and combining them into a new Huffman tree, and finally putting that back onto the priority queue. We do this until the final tree is all that is in the queue:

while(huffQueue.size() > 1){

leftTree = huffQueue.poll();

rightTree = huffQueue.poll();

tempTree = new HuffmanTree<Character>(leftTree, rightTree);

huffQueue.offer(tempTree);

}Once we have the tree we can begin building the codes used to compress the data. Building the codes follows a simple algorithm: starting at the root of the Huffman tree we will traverse until we reach each leaf node. The path taken to the leaf will determine the code; every left we take is denoted a 0 and every right we take is denoted a 1. We will store the character and codes as key-value pairs in a hashmap:

private HashMap<Character, String> buildMap(HashMap<Character,String> codeMap,

HuffmanTree<Character> huffTree,

StringBuilder code){

if (huffTree.symbol != null){

// Put the <Symbol,Code> pair in the map

codeMap.put(huffTree.symbol,code.toString());

} else {

// Traverse left

code.append(0);

codeMap = buildMap(codeMap, huffTree.left, code);

code.deleteCharAt(code.length()-1);

// Traverse right

code.append(1);

codeMap = buildMap(codeMap, huffTree.right, code);

code.deleteCharAt(code.length()-1);

}

return codeMap;

}To write out the compressed file there are two main steps remaining. First, we need to encode some sort of header so that we can recover the data. Second, we will go through and replace each character in the original message with the Huffman code from our hashmap. To write out the header we will encode the Huffman tree by writing the structure of the Huffman tree:

private void writeHeader(BinaryWriter output, HuffmanTree<Character> huffTree){

if(huffTree.symbol == null){

output.write(0);

if(huffTree.left != null) writeHeader(output,huffTree.left);

if(huffTree.right != null) writeHeader(output,huffTree.right);

}else{

output.write(1);

Integer symbol = (int) huffTree.symbol.charValue();

output.writeByte( Integer.toBinaryString(symbol) );

}

}Next we simply have to parse through the original text and replace the characters with their associated Huffman code:

while( (line = reader.readLine()) != null ){

for(char codeChar : line.toCharArray()){

// Get the code for each character

code = codeMap.get(codeChar);

// Write bitwise

for( char bit : code.toCharArray() ){

output.write((int) (bit - 48)); //Scaled for ascii

}

}

}Once this is done we just have to write the bits to a file. Doing this in Java requires some additional work that will be touched on in the Java Implementation section.

Huffman Decoding

The act of decoding our compressed file is essentially reversing the last steps of the compression process. We will begin by reading in the header and reconstructing the Huffman tree. We will accomplish this by reading the header bit-by-bit; if the bit is a zero we must look further down the header, which means another branch must be added to the Huffman tree. Once we encounter a one we have found a leaf node and can convert the next 8 bits into an ASCII encoded character. The code for this operation looks like:

private HuffmanTree<Character> buildTree(BinaryReader bitreader){

int bit = 0;

int symbol;

do{ // while (bit != -1 && eof != true)

bit = bitreader.read();

if(bit == 1){

//Found a leaf node

symbol = bitreader.readByte();

if(symbol > 0){

return new HuffmanTree<Character>((char) symbol, 0);

}else{

eof = true;

}

}else if (bit == 0){

// Look further down the header

HuffmanTree<Character> leftTree = buildTree(bitreader);

HuffmanTree<Character> rightTree = buildTree(bitreader);

return new HuffmanTree<Character>(leftTree,rightTree);

}

}while(bit!=-1 && eof!=true);

return new HuffmanTree<Character>((char) 0,0);

}From this we can build the map of characters and codes. This is accomplished the same way as previously. Now that we have the mapping of characters to codes we can loop through and decoded the compressed file. The beauty of the Huffman encoding is the ability to decode so easily. Thanks to the structure of the Huffman tree no codes are substrings of any other codes, meaning that there is only one way to interpret a stream of codes. We can decode easily:

private String decode(BinaryReader bitreader,HashMap<String, Character> codeMap) {

StringBuilder code = new StringBuilder();

StringBuilder decoded = new StringBuilder();

int bit = bitreader.read();

do{

code.append(bit);

if (codeMap.containsKey(code.toString())){

decoded.append(codeMap.get(code.toString()));

code.setLength(0);

}

bit = bitreader.read();

}while(bit!=-1);

return decoded.toString();

}Java Implementation

The default method of handling binary files in Java leaves something to be desired for Compressure application; there is no direct method to interact with files in a bit-wise manner. To account for this we will have to develop our own helper classes to write and read the compressed files. As seen previously in the code these helper classes are named BinaryReader and BinaryWriter. These classes work by keeping an internal byte sized buffer that is written to bit-wise by shifting. For example, the writer’s main writeBit method is as follows:

theByte = theByte << 1 | bit;

currentBit++;

if(currentBit == 8){

output.write(theByte);

currentBit = 0;

}Analysis

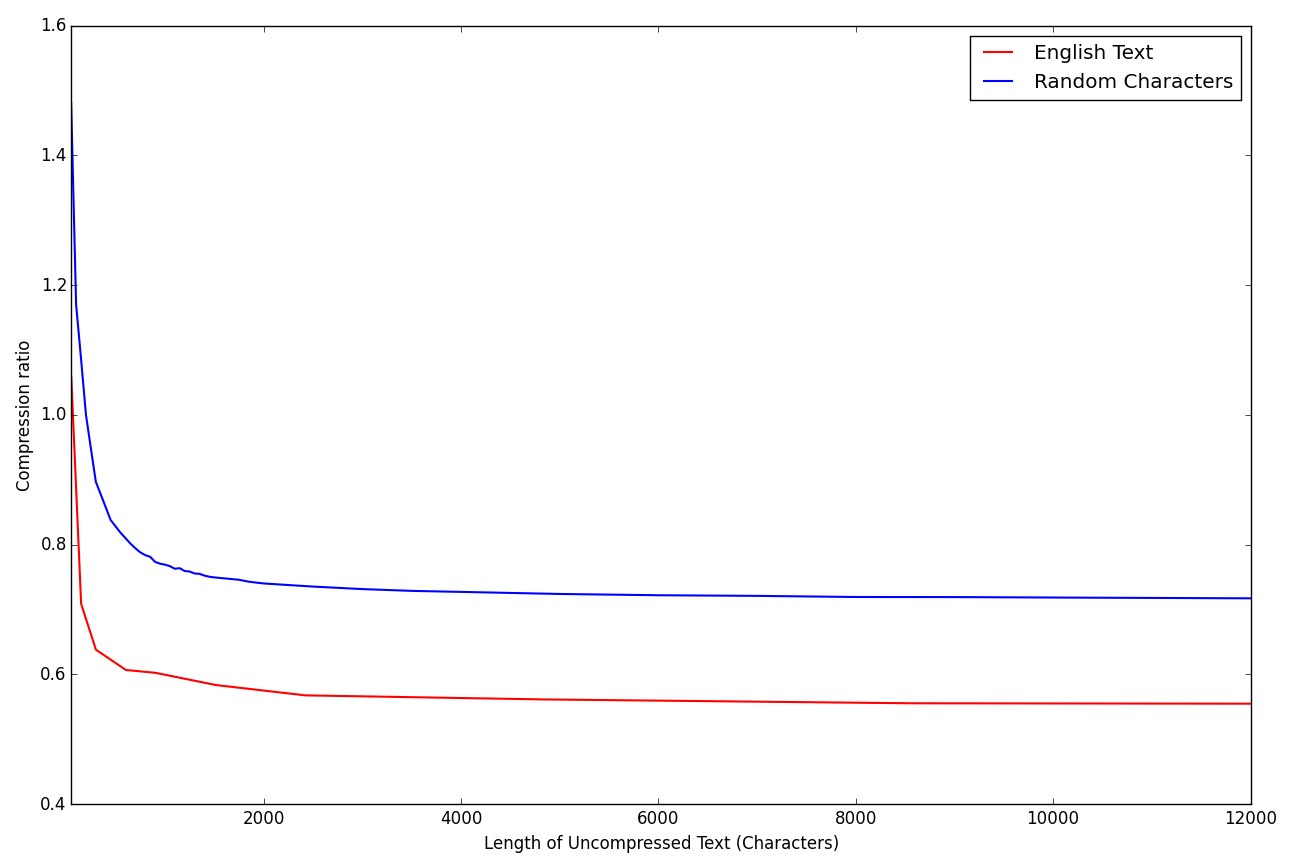

So how much compression can we actually obtain from a simple method like this? To find out I have compared the compression rate of both English text and randomly generated ASCII characters. For the random tests I generated there were 50 randomly selected characters. To encode 50 distinct characters using a fixed length encoding you would need to use 6 bits, which would result in a compression rate of 0.75 from the UTF-8 alphabet. For large text files using the randomly generated texts the Compressure application achieved a compression rate of approximately 0.75, in line with our predictions. For an English text however, Compressure does actually achieve some notable compression. For large files a compression rate of approximately 0.6 was achieved. For small files it can be seen that writing the header actually caused the “compressed” file to become larger.

How does this stack up to real compression programs? Using an input file of approximately 20,000 characters the resulting Huffman compressed file was 10.8 kB while a version of the same file compressed with the GNU tar utility was only 7.6 kB. Both showed great improvements over the original file size of 19.6 kB, but it is clear that the methods developed here are too simplistic to be useful contenders.

Conclusion

Regardless of the usefulness of the methods developed here, it is always beneficial to have at least a basic understanding of the processes that underly technologies that are so commonly used. The Huffman encoding technique was a major milestone in data compression techniques, and many of the advanced methods that have been developed since the 1950’s are based on the original paper. Adaptive Huffman encoding, which can compress data in real time, reducing the need to complete multiple passes over the original data. Another popular technique based on Huffman encoding simply encodes groups of characters rather than individual ones. Both of these methods provides specialized treatments based on the requirements and initial data supplied. Like all things, data compression requires intelligent decisions to be made to maximize their successes.

If you would like to play with the Compressure application you can clone the code from https://github.com/arbennett/Compressure.git.

References

[1] A Method for the Construction of Minimum-Redundancy Codes